It’s no secret that Gandhi’s approach to fighting against oppression was unique and unconventional. Even today, it’s challenging to fully comprehend it. After all, the struggle for freedom in popular history is often romanticized, portraying a weak fighting against a powerful force, relying heavily on inner strength and sometimes employing clever tactics to overcome the brute and sometime inhuman force of oppressors. For instance, take the example of the David and Goliath folklore: when everyone was afraid to fight a giant Goliath, here was the young David armed with faith, courage, and smart fighting for his people. Of course, the struggle between oppressor and oppressed was/is an extraordinary event, which is why it’s often romanticized. History is filled with such stories from around the world.

In this context, the Indian freedom struggle under Gandhi stands out as an unusual case: it was based on nonviolence. Imagine David, with all his courage, standing before Goliath and proclaiming, “I will not harm the Philistines.” In what universe would that have led to victory for the Israelites?

So, naturally, when people hear about Gandhi, they ask, “How can a fight for something like freedom from oppression be nonviolent? Why would a powerful oppressor willingly relinquish control over the oppressed? Isn’t all the talk about changing the hearts of oppressors illogical, purely philosophical, and not practical in the real world? Or like many Gandhi haters proclaimed was Gandhi merely a stooge of the British Empire, who allowed them to rule India by manipulating the masses?”

Usually, even people like me who believe in Gandhi tend to focus more on his moral, philosophical, and religious aspects of his leadership. However, a deeper exploration of Gandhi’s leadership reveals a more cohesive narrative: one that was both unusual and effective. My inspiration to study Gandhi comes from Nelson Mandela, who delved into Gandhi’s life and teachings far more extensively before drawing inspiration from him. What resonated with me was Mandela’s strategic perspective on Gandhi, which went beyond the usual facade of respect for Gandhi’s values while rejecting his methods as too idealistic and impractical. In this article, I would like to share my thoughts on the strategic aspects of Gandhi’s leadership and welcome your feedback to further develop my understanding.

To understand Gandhi and his ways I first like to understand the freedom struggle before Gandhi: its characteristics, its advantages and perhaps limitations. Once we go through it, perhaps we can understand modern colonialism of 20th century. This should set a context for us to understand Gandhi, his method, how they were effective or ineffective. This should also help us with more contemporary world to explore, where can Gandhi’s method might be useful.

Freedom Struggles Before Gandhi

The British (the British East India Company and the British Empire) ruled India for a staggering 200 years. During this period, Indians fought against the British through various means and for various reasons. Let’s examine some of these struggles that preceded Gandhi’s approach.

1857 uprising

The British East India Company secured its dominance over India at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, followed by a century of gradual tightening of its grip. Initially, the company collaborated with local leaders by dividing governance responsibilities. However, by 1800, the company’s ambitions led it to devise schemes to discard local rules from the governance structure and achieve sole control, angering the local rulers. At the same time, the company disregarded socio-religious issues that deeply hurt the sentiments of the commoners, culminating in the “greased cartridge controversy” and the eventual revolt of 1857.

The British crushed the revolt with immense force, but it brought about lasting changes. The revolt marked a shift in India’s governance from the company to the British Empire. British leaders realized that a capitalist company driven solely by short-term profit was not an appropriate way to rule. This necessitated the British crown takeover of India from the company. However, it is important to note that the although the ruling body changed, the core principle of rule stayed same: for the benefit of British capitalism, albeit with long-term interests. The crown took over India from the company, while the company focused on maximizing profits within the framework of the empire.

From the perspective of Indians, the 1857 revolt holds a romantic place in Indian history. It was the first time Indians mounted a credible opposition against British rule. Although they ultimately lost the battle, their courage inspired future generations. For example the Queen of Jhansi remains a symbol of courage and resistance for her fight for the rights of her adopted son. On the other hand, it’s also true that the revolt failed to unite the common people. In essence, it was a struggle between local emperors fighting for their empires and their pride. While many people fought for these emperors with loyalty, most did not. For instance, the Sikhs from Punjab did not align with the revolt because they knew it was essentially a fight for the Mughal empire, the arch enemy of Sikh faith. The revolt ultimately ended the struggle for freedom through a battle of empires by weakening the feudal structure of India to the point where it never challenged the British again.

Early Indian National Congress (INC)

After the local empires failed in the revolt of 1857, the struggle against British rule shifted towards social movements based on Western (modern) principles such as political representation, self-governance, and social and political awareness. Essentially, an elite of Indians educated in Western ideologies and principles began to advocate for these same rights and principles in India, but in a moderate and reformist approach. And indeed, some British sympathized with them. This is how the Indian National Congress (INC) came into existence with the help of Allan Hume, Dadabhai Naoroji, and others.

During this phase, the Indian freedom struggle began to demand freedom and self-rule, as discussed in Western philosophy. The famous proclamation by Tilak, “Swaraj (self-rule) is my birthright, and I shall have it,” encapsulated this sentiment. Annie Besant’s call for Home Rule in India was another such drive. Additionally, there were nationalistic movements in the form of Swadeshi (self-reliance), boycott, and national education. There were also efforts to raise social and political awareness through education, newspapers, and other means.

From an Indian perspective, the early INC played a crucial role in shaping the struggle for independence and self-determination. Early Indian National Congress (INC) marked a significant shift in the freedom struggle, moving away from empirical battles towards more social moments. It was based on modern principles and inclined towards moderation, and reforms. However, the struggle was more philosophical in nature, driven by an elite educated in Western education. While there was progress from a few feudal fighters against the British Empire to a large number of educated, literate elites fighting for reform, the movement was not mass-based. I could imagine that for a commoner from a village, self-rule meant nothing. It held significance for those educated in Western education but held no meaning for the common man. There might have been some sense of nationalistic pride through Swadeshi and national education, but on the ground, there was still the question of what freedom meant in daily life. For someone who always had an emperor, the concept of self-rule was foreign. That’s why I believe there was apathy among the masses of India towards the early INC’s work.

Understanding the British Raj

Before we delve into Gandhi and the Indian freedom struggle, let’s understand the British Raj. What was it, how did it function, and why it differed from previous

Empires during the Industrial Revolution: Empires have been a part of human history, but their nature has evolved over time. Early empires like Alexander’s and Genghis Khan’s conquests were driven by a desire for glory and pride. On the other side the Mughal Empire of India was a political necessity and an opportunity. But if I had to summarize ’To be the first to conquer the known world’ might have been their moto. Yes there was also an element of self enrichment through spoil and loots but that wasn’t the driving focus for the conquerors. After all why would Alexander travel to Indian subcontinent and die on way back, if not for glory.

However, this changed after the Industrial Revolution. With the Industrial Revolution, capitalistic companies became the driving force in West. Companies like the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company ventured to places where no one from the West had gone, seeking resources and markets, driven by the sole purpose of maximizing the value for their stakeholders.

As you may have noticed, the Battle of Plassey wasn’t fought by the British Crown but by the British East India Company to expand its business interests. The primary objective of the battle was to secure favorable business and trade terms in India, either from local rulers or, if necessary, through the company’s rule. Essentially, the goal was to ensure that the company obtained resources, the necessary infrastructure, and labor at the lowest possible cost while simultaneously maintaining a monopoly and exclusivity in the market. And one mission that was driving all this ‘maximize profits’ for stakeholders.

After 1857 revolt, the governance responsibility shifted from the company to the British Crown. But that can be explained by considering typical behavior of capitalistic organizations and its executives: maximize profit in short tenures, which as we discussed above backfired.

However even though the Crown took owner the responsible for governing India after 1857 the basic context did not change: the colonism was driven by capitalism. The only difference was that now decisions were not made by short sighted executives but a crown that wanted the capitalistic enterprise prosper for long term. Following image describes colonialism of 20th century as emergence pheromones from modern capitalism and imperialism.

Gandhi’s Leadership in time of colonialism

Now that the context is set to understand Gandhi and his leadership, I structurise Gandhi work in three key elements.

Understanding the dynamics of oppressor and oppressed: non violence

Usually, when we envision conflict between two groups, we visualize two equals. However, this is often incorrect, especially in the context of oppression. Oppression is inherently a power imbalance, a dominant force oppressing a weaker one against their will. For instance, the East India Company sought trade terms favorable to them over other companies, including local ones, and resorted to force to achieve this. The power disparity between the colonial power and its subjects persisted throughout the struggle, even in the mid-21st century, when the armed Indian struggle often sought to collaborate with external powers (such as Bose with the Germans and Japanese) to compensate for its limitations against British forces.

However, power dynamics can take further sinister turn, as explained by Nelson Mandela in his book ‘Long Walk to Freedom’: “Oppressors typically hold a position of strength, and any attempt to confront them with violence often results in a crushing blow to the movement of the oppressed. Moreover, it is not uncommon for oppressors to justify the use of brutal force, as seen in the Jalianwala Bagh massacre, the lynching of black Americans in the United States, and the apartheid regime in South Africa’s brutal suppression of the ANC.

Therefore, understanding and acknowledging the power disparity between the oppressed and the oppressor is crucial in combating oppression. Using violence to fight against an oppressor is often a decision that should not be made lightly. While armed conflict is always an option, it does come at a significant cost of lives for resistance. History might make it sound romantic but in reality losing lives is never something to cherish.

After the 1857 revolt, the Indian struggle against British rule transitioned to non-violent methods through the Indian National Congress (INC). However, Gandhi further refined this approach, making it non-confrontational. For example, Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement in the early 21st century did not involve protests or rallies. Instead, it simply asked people to cease working for the British government, rendering the entire governance system ineffective.

Nevertheless, non-violence alone is insufficient for achieving success in the fight against oppression. Gandhi recognized this and combined it with other aspects, as explained below, which often elude people’s understanding.

Moving from fight of empires to mass movement:

The 1857 revolt marked the end of the era of battles between empires, paving the way for the shift towards bottom-up mass movements. The Indian National Congress (INC) played a pivotal role in driving these moments through principles such as representation, freedom, and self-rule. Additionally, the INC actively fostered social awareness to build up mass mobilization. However, for the most part, its efforts remained for an elite educated class rather than truly reaching the masses. In my opinion, the INC failed to effectively communicate the meaning of freedom to the common people.

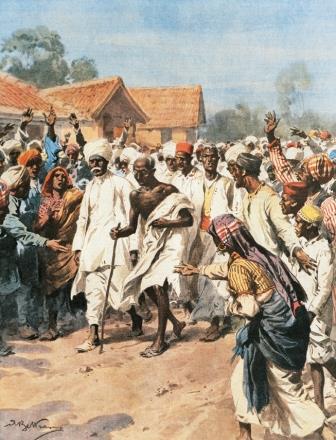

Gandhi introduced a transformative change that addressed this issue. For instance, consider the first movement initiated by Gandhi in India, the Champaran Satyagraha of 1917. During this period, the British Empire was driven by capitalism, seeking to acquire resources at the lowest possible cost. In Champaran, farmers were compelled to cultivate Indigo, a crucial resource for the textile industry, without receiving adequate compensation. Instead, the farmers yearned to grow food and other products to feed and sustain their families. It’s an intriguing story of how Gandhi worked with this movement, which could be the subject of another discussion. However, for the purpose of this discussion, what matters most is how he defined the concept of freedom. Prior to Champaran, freedom was proposed as a birthright (as Tilak declared) or home rule (as Besant proposed), both of which held philosophical merit. However, at Champaran, Gandhi defined freedom as the “ability of the farmer to grow food for his/her family,” as simple as that but far more grounded and relatable to the people who truly mattered. Champaran was not an isolated incident; every movement initiated by Gandhi was connected to the people and their concerns. This was a revolutionary aspect of the new resistance.

Focusing on the very foundation of colonialism: capitalistic interests

The British referred to India as a crown jewel in their empire, but it wasn’t the beauty of the crown or the pride of the empire that fueled colonialism. As we repeatedly discuss this topic, it becomes evident that capitalism was the driving force behind colonialism. The primary objective of colonies was to allow enterprises to maximize profits at the expense of the colonial subjects.

The indigo farming case discussed above was closely related to the textile industry. In fact, the textile industry was the primary catalyst for Indian oppression. In the context of India, British companies acquired cotton from the subcontinent at the lowest possible price. They constructed infrastructure to transport that cotton, imposing taxes on Indian citizens. Subsequently, they became the sole sellers in India, aiming to maximize profits. Along the way, they destroyed the Indian textile industry, the cotton producers, and the Indian population in general through taxes. Ultimately, the Indian consumer was burdened with higher prices due to the monopoly.

The movie Gandhi depicted this reality in a powerful manner. Gandhi witnessed a woman washing her only cloth naked in a river, which deeply moved him and led him to renounce cloths for the rest of his life. However, this pivotal moment also marked a turning point in Gandhi’s approach. Inspired by this, Gandhi simply urged people to spin a wheel (Charkha) to make their own cloths. There was no need for protests or agitation; people were simply asked to sit at home and spin their own cloths. Through this simple act, the spinning wheel became a symbol of India’s resistance. Remarkably, without resorting to violence, the movement managed to address the root cause of exploitation. Isn’t that profound?

Take another example, the salt march, which exemplifies all these aspects of Gandhi’s fight against colonialism. Salt production is a simple process: gather sea water, let it evaporate, and voila! You have “salt.” Salt holds a special place in Indian cuisine; there’s hardly a dish in India that doesn’t require salt. In fact, the absence of salt in food is enough to make Indians consider it unappetizing. In this context, the British government decided to ban salt production for individuals and impose a tax on it. This was another way for them to extract wealth and use it to fund infrastructure for businesses. Gandhi recognized the significance of salt. He once again linked salt to the struggle for freedom and understood the importance of this tax to the British government and companies. Consequently, the salt march became a memorable movement in India’s fight against colonialism.

Conclusion

The Indian freedom struggle under Gandhi was unique in its nonviolent approach, challenging the traditional narrative of oppressed fighting against oppressors. To understand Gandhi’s methods, it is crucial to examine the freedom struggles before him, including the 1857 uprising and the early Indian National Congress. These struggles, while significant, lacked mass support and a clear vision of freedom for the common people.

Gandhi’s leadership against colonialism focused on non-violent resistance, mass movements, and attacking the foundation of colonialism: capitalism. He understood the power imbalance between the oppressed and the oppressor, emphasizing the importance of non-violent methods. Gandhi’s movements, such as the Champaran Satyagraha and the Salt March, directly addressed the concerns of the people connecting the meaning of freedom to real people. Whereas strategically he aligned his fight against, capitalistic interests which were core of the colonialism rather than fighting the superficial fight about empirical pride or principle of self rule.

But thats past isn’t it? What it means for us today. For me the leadership lessons are strategical as well as moral.

Some time we even as leaders are in emotions leading to flaring temper. But we must be always mindful of realities of struggle and have strength to sustain. If the struggle is between oppressed and oppression, more often than not the oppressor hold certain powers that makes the battle uphill for oppressed ones. Understanding and acknowledging those power disparities is key.

Second is about connecting with your people. As leader vision, missions are great, principles strategies are even better but what do they mean for people? In case of Gandhi freedom ment that a farmer could provide two meals for family and a lady could get two sets of cloths without going brook. Any mission we undertake we must connect to people and understand what it ment for them.

Finally it’s about understanding the context. Sometimes the reality has changed and we dont make efforts to understand it. In case of imperialism it changed from pride driven endeavor to a capatilistic exercise in form of colony. Understanding the problem to be solved the context is key. As they say well understood problem is …….

Wonderful post 🌅🎸

LikeLike